Antique Early Gate mark Gatemark Cast Iron Skillet 1850 Fancy Handle Frontier

This one isn't kitchenware so much as frontier hardware with a pulse. Before doctors washed their hands on purpose. This skillet was already earning its keep. Picture it: a horse tied to a hitching rail, a canvas bedroll thrown over the saddle horn, and this pan riding low-blackened, seasoned, trusted.

It cooked bacon at dawn, cornbread at dusk, and whatever could be hunted, trapped, or traded in between. It didn't care whether the fire came from a hearth, a chuck wagon, or a shallow pit scraped into prairie soil. This is not a decorative antique pretending to be old. What we're looking at.

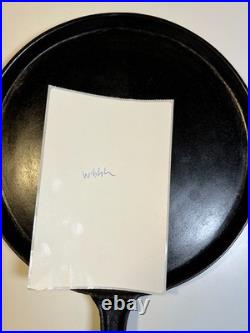

Bottom: clear gatemark (early sand-casting scar). Handle: elongated, refined teardrop loop - unusually elegant for the era.

Seasoning: deep, natural, glassy black patina from long use. Heavy, honest buildup around outer edges.

Tiny wobble (typical for hand-cast pieces; does not affect use). That gatemark alone puts us firmly in pre-industrial American ironwork territory. Dating it as precisely as possible. Here's why that window fits.

Gatemarks are scars left where molten iron entered the mold. Common before 1850, increasingly rare after. By the 1860s, bottom gating largely disappears in favor of side or sprue systems. This one is clean, centered, and unapologetic - classic early work.

Long, narrow, refined loop suggests earlier hand-pattern carving. Later 19th-century pans trend thicker, more standardized, less elegant. This handle wasn't designed by committee - it was shaped by a patternmaker with time and skill. Thinner, more deliberate casting than later mass-production.

Early iron was expensive; excess weight wasn't wasted. By late 1800s, pans get bulkier as foundries chase speed over finesse.

Taken together, this pan almost certainly predates the Civil War-and quite possibly predates the invention of the revolver as we know it. Life when this pan was born. Stoves were wood-fired, coal-fired, or nonexistent. Opium and mercury were standard treatments. Germ theory hadn't caught on yet.

The United States was still arguing about what it even. Andrew Jackson, then Martin Van Buren, then William Henry Harrison (briefly) held office.

Meals were cooked from scratch, over fire, daily. A good pan could mean the difference between eating well and going hungry. Iron cookware was passed down-not replaced.

This skillet likely fed multiple generations before anyone thought of calling it antique. Why it feels so right in the hand. There's a reason it feels. The handle length keeps knuckles away from flame.

The seasoning tells you it's been used-not displayed. This one taught them how. If you're the kind of person who feels a little thrill holding something that was already old when railroads arrived-this is your pan.

Hang it, cook with it, or just let it sit somewhere visible and heavy with history. Either way, it doesn't whisper. And if someone asks where you got it?

Just say: From a time when things had to work.